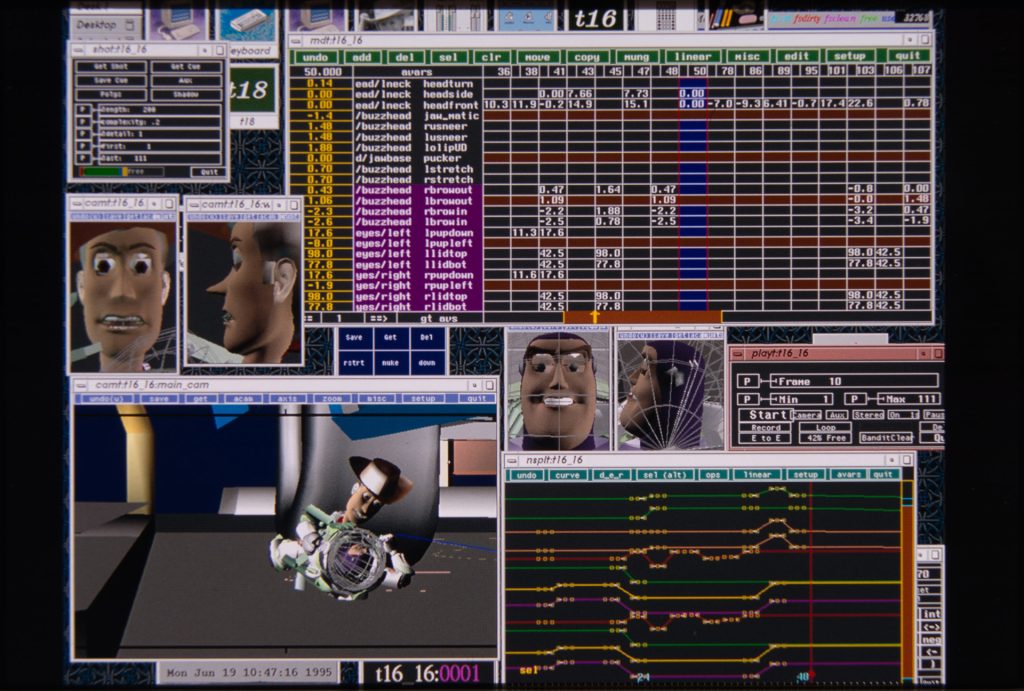

When Toy Story was released in theaters on November 22, 1995, it not only won over audiences around the world, but it put Pixar Animation Studios on the map. As the first fully computer-animated feature film, it was considered a gamble — one that paid off, as it opened at No. 1 and went on to become the highest-grossing movie of the year, earning $192 million domestically and $362 million worldwide. Toy Story went on receive a Special Achievement Academy Award® and earned Oscar® nominations for Best Original Song, Best Original Score, and Best Original Screenplay, marking the first time an animated film had been recognized for screenwriting.

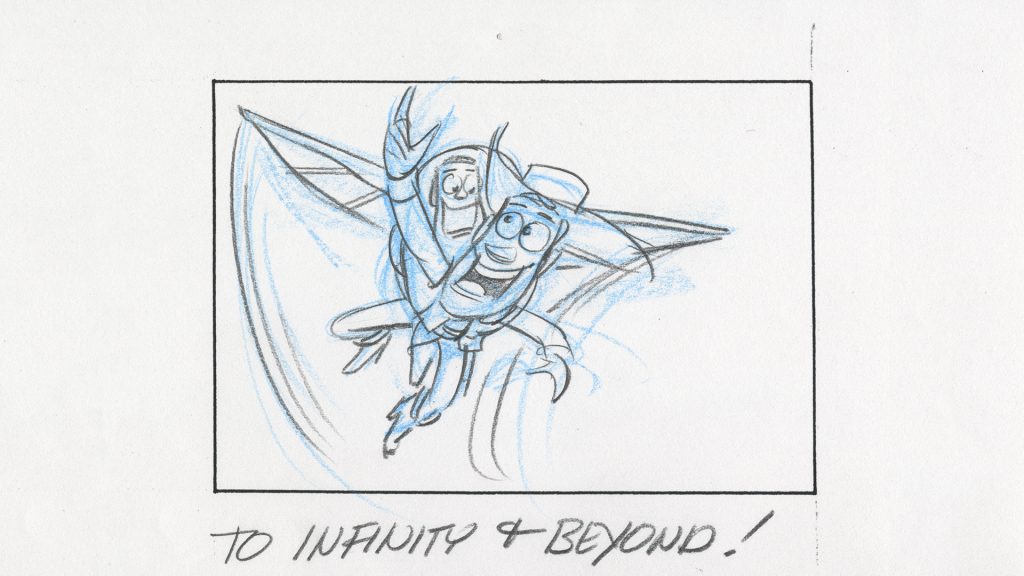

Andrew Stanton — Pixar’s second animator and ninth employee — was one of four screenwriters to receive an Academy Award nomination for his contribution to Toy Story. In addition to this, on the original Toy Story film Stanton is also credited as a character designer and story artist, and provided an additional character voice. He went on to receive credit as a screenwriter on many subsequent Pixar films, in addition to directing Finding Nemo (2003), WALL•E (2008), and Finding Dory (2016). He currently serves as Vice President, Creative, overseeing all feature projects at the studio, and he is writing and directing Toy Story 5, opening exclusively in theaters on June 19, 2026.

As the Toy Story 30th anniversary celebration continues this week — the Buzz Lightyear balloon returns to the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade on Thursday — Stanton reflected on Toy Story‘s origins and legacy.

Before Toy Story, Pixar had never produced a feature-length film before striking a three-picture deal with Disney. What set the studio apart back then — and what still sets it apart today?

Everything was very character-based, even then, and story-based — even though we didn’t know much about how to write or make a feature film. We knew how to tell a good yarn, how to make you laugh, how to make you be entertained. And that was the driver behind everything we did, whether it was a short film or a commercial. And that’s stayed consistent ever since.

The same thing sets us apart today: story, story, story.

How we’ve chosen to evolve technology, how we’ve chosen to explore it, [and] how we’ve chosen to operate it has all been driven by the stories we want to tell. Even when we were making commercials, we would bid on things that we couldn’t do because we loved the idea so much that it gave us fuel to want to figure out how we could do it. And we are the very same way now. We just wait until there’s a story and a situation and characters that excite us so much that [we feel motivated] to want to figure out how to make something.

What are the hallmarks of a quintessential Toy Story story?

As a writer and a filmmaker, I don’t like making guardrails. Although, over 30 years of making up to five Toy Story movies now, there have been some clear lanes or parameters.

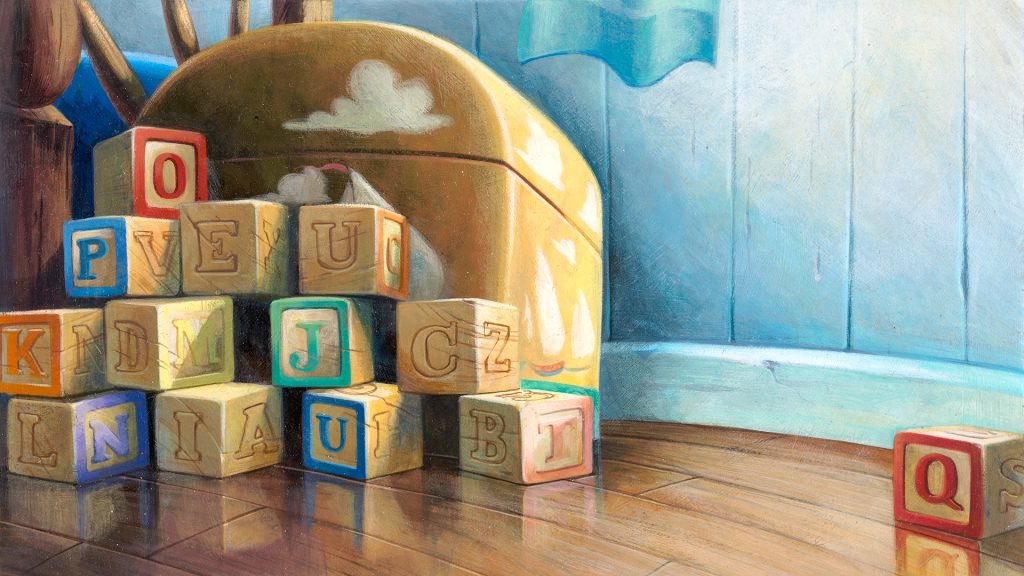

One, of course, is that it’s about toys. But the other thing is that [each film] deals with some truth about growing up… There’s always some new aspect of toy life that you’ve never seen, from a different perspective, that we like to add to the quilt of the world. And there’s always some new type of toy that you can add to the cast of characters. The world is so vast… Every household’s a little different, every kid’s a little different, every style of play is a little unique to the thumbprint of the owner and to that toy’s experience. Nobody played with exactly the same things growing up, so you could compare notes forever; it’s like comparing record collections. There’s some overlap, but there’s so much variety.

How has Pixar continued to raise the bar creatively and technologically in the 30 years since Toy Story‘s release?

Nobody’s ever said, “What should we figure out? What should we conquer?” Those are always just byproducts of the next story we want to tell. All I’ve ever been in conversations with is: “What would you like to see that you haven’t seen before with Woody or Buzz? What would you like to see with Andy’s life or Bonnie’s life? What scenario have you not experienced yet?” It can be something as simple as we left an RC car out in the rain. Leaving a toy out in the rain had never been touched after three [Toy Story] movies. The thing that people expect or assume is that we have to do to something more [spectacular].

But, if you think about it, a kid’s life with toys is anywhere from 5 to 10 years, and that’s a lot of that’s a lot of time in the house being played with. All those in-between moments, all those simple moments — like a toy being left outside or forgotten behind a couch — are life’s moments for these toys that we can make narratively interesting. They don’t have to sound sexy to the outside world. They just have to be viscerally authentic to [each character]. That’s the real juice of a Toy Story movie — the truth of what it’s like to be a toy.

You’ve been a co-writer on every Toy Story film. What makes the world you’ve created so rife for storytelling, and how were you able to evolve with the audience over time?

I’m surprised myself how much we can continually get out of the Toy Story world. Not every film and subject matter can do this. I think the main reason is that we can embrace time. We can grow old with the kids… Let Andy grow up. Let the toys be handed off. Let one of them separate. Let them somebody be forgotten. These are all things that really happen. The minute you are in a flea market and you buy a used toy, or you lend a toy to somebody else and they never remember to give it back, that’s a whole ‘nother movie right there! You can embrace time, and we have… Time has moved forward with all of these characters, and that’s the key. The key is not putting them in amber and trying to honor them. The key is letting them change, like life changes.