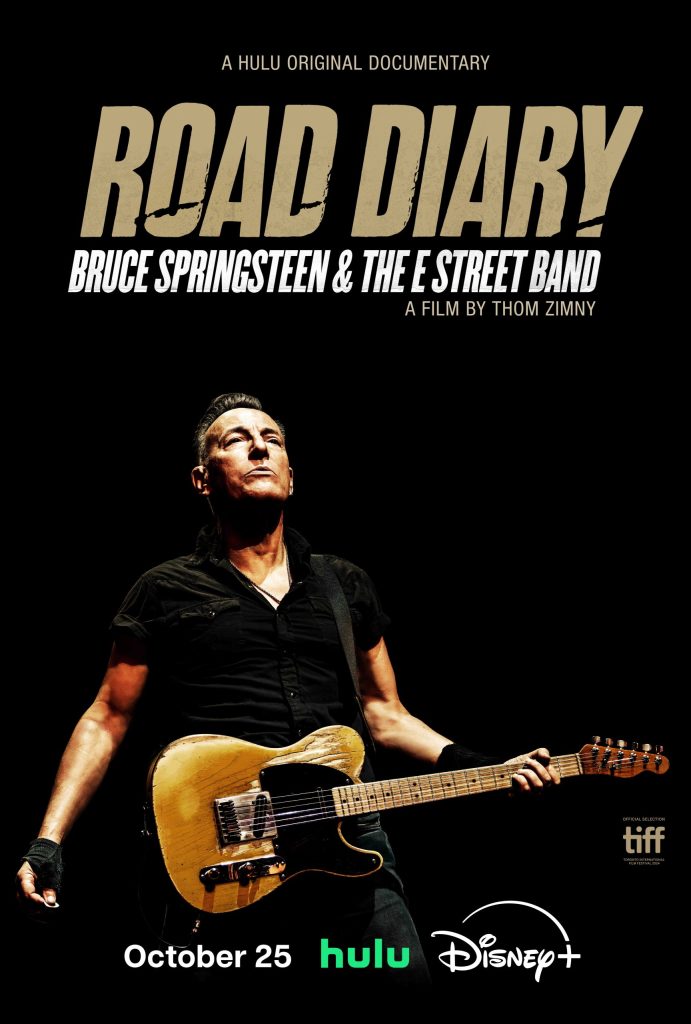

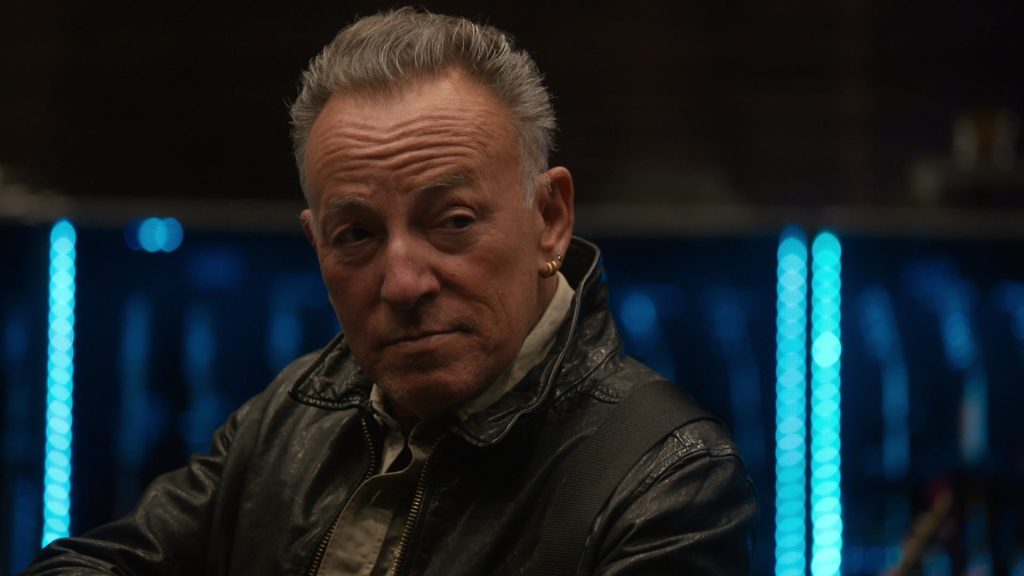

In Road Diary: Bruce Springsteen and The E Street Band, which premieres on Hulu and Disney+ Friday, October 25, the legendary singer reconnects with his band — and his fans — after six globally tumultuous years to reaffirm the ties that bind with the added perspective of age and the limitless energy of rock and roll.

Emmy® Award winning director Thom Zimny — whose work with the Boss stretches back nearly 25 years — orchestrates the project with a level of authenticity and soulfulness often unseen in traditional concert films. From the tour’s early prep and rehearsals to the cross-continent performances before hundreds of thousands of fans, Zimny details the current creative process of an artist who’s worshipped at the altar of rock since he bought his first guitar in 1964.

Zimny talked to us about alternating between fan and filmmaker as he experienced and filmed the performances and then edited the footage. As a fan he was able to rejoice in the music, but as a documentarian he worked hard to capture the multifaceted nature of a dynamic performer debuting new songs while finding new meaning in the old ones.

Why did you gravitate toward music and chronicling music?

I’m dyslexic. Growing up, I lived in a world of pure chaos, not being able to read or write comfortably and wanting to express myself. That gave me a connection to visuals and music, a space to dream. I listened to music very religiously. It was a messenger of sorts, in that it could tap into feelings. And I started to play around with editing and music. Actually, one of the first films I made was using a Bruce Springsteen song.

Were you a Springsteen fan growing up?

My first Bruce show was on “The River” tour. I was 18 years old. I hold on to all those memories of growing up on the Jersey Shore, the small-town element and how important the music was to me.

Community is such a strong aspect of the film.

Road Diary is about the conversation that Bruce has had for the last 50 years with fans. There was a community there that I wanted to tap into and show. I think that understanding of community for me came in the early days of being in Jersey and trading tapes and talking about the mystery of the live show. How can we get tickets? Will Bruce show up? All these elements create a bit of a rock and roll energy and myth. I never let go of that stuff.

The shared past is a huge part of Springsteen’s bond with the audience.

I wanted to tap into E Street history, but I also wanted to show Bruce the artist right now. He was telling a story with this set list, and it’s a story that we’ve all been part of. He was using new songs and old songs and building a narrative. A song that you’ve had a history with, like “Backstreets”, changes with Bruce putting it up against a new song, like “Last Man Standing”. I’ve had my own love of certain songs, but now it feels different since we’ve gone through so much with the lockdown. Those are the kind of themes I was chasing early on with the film.

How quickly did you identify those themes?

I don’t think I was very conscious in the beginning days. I try not to create a locked point of view. I tried to stand before the band, the artist, [manager] Jon Landau, and watch them as much as I could and then went back to the editing room. Within a few months, I could see that the songs Bruce picked and how he arranged the set list had a feeling, a tone, that was dealing with themes of reflection, of mortality. It was a perfect emotional place to stay because Bruce is creating music in the moment, but he’s also looking back. And I knew that was a storyline to chase. It broke away from the cliches of rock and roll, opened up the door to relate to the uber fan, but also to someone who’s new to the music.

Did you ultimately find the story in the editing room?

The film gods throw you a lot of great mistakes if you keep your eyes open. I learned from Jon and Bruce to be present, be prepared, but be ready for an audible, a curve ball, something that’s thrown your way. Sometimes it’s archival footage that you stumble across or sometimes you’re filming and you just see.

For example, I filmed Bruce going up the stairs in a certain way, and it felt very heroic and it finds its place in the film. I let the film talk to me. The film will give you direction. Some of the great things are turning over that sense of control that you’re directing everything and forcing a POV. The film, if you pay attention, will tell you where it wants to go.

At one point in Road Diary, Springsteen says if he makes a mistake, then that’s the moment. Sounds like that’s your process also.

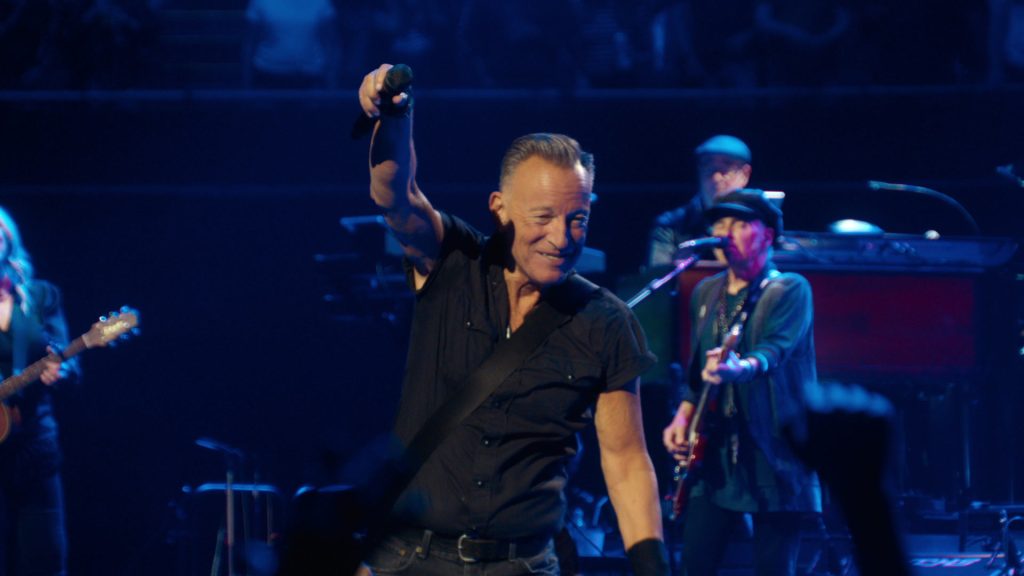

That’s the influence I’ve had being around an artist who takes these sorts of chances and is open to the spontaneity and the beauty of things just happening. I’ve watched Bruce in the middle of the show change the set list and change the emotional arc. These are things that I try to reflect in Road Diary. This movie stands in the shadow of a Bruce show.

Can you explain that thought a little more?

It picks up the emotional tones that the actual show itself has: laughter, humor, rock and roll, energy, reflection, sadness, moments of quiet to reflect, the sense of life ending, and what we’re doing in the moment. I can’t verbalize that, but I tried to capture it in this film. That’s why I focused on people’s eyes, their expressions, their moment of transition, where they have a certain set of feelings and they’re connected so deeply to Bruce and the band and the sonic quality and the beautiful storytelling and the writing. You see it in someone’s eyes.

Springsteen narrates and he interacts with the band, but you don’t interview him like you do the band members. Why that choice?

I use Bruce and his voiceover as a quiet, reflective voice sitting across from you in a diner or at a bar, saying thoughts and observations and confessions. That’s one voice. The other is having the band before you right now and putting them against archival clips so you see their history, and see them engage before the camera, telling fantastic stories. I wanted Bruce’s voice to be whispering in your head. In some ways, these thoughts are much more personal and more detailed than some of the interviews in the rest of the film.

The film flows like a conversation.

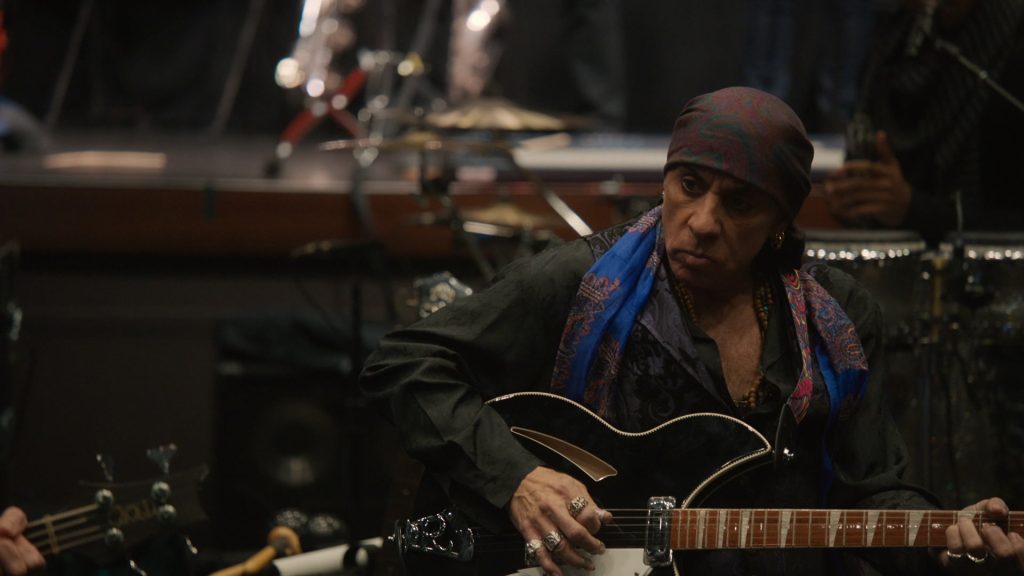

The great thing of working with Jon and Bruce for the last 24 years is the gift of time and trust. I was able to sit with the band for hours, and in that comes conversation. There are no boundaries. So you get [guitarist] Steven [Van Zandt] saying, “I’m the musical director now; it’s 40 years too late.” That’s what we wanted from the interviews on an emotional level. There’s no forced agenda or narrative. And people are being honest.

Do you consider this to be a performance film?

Good question. I don’t know. There’s no genre that I can lock it into, because it goes from cinéma vérité to rock concert footage to spoken word. This film plays with all the different languages, or at least we try.

For you, where does the fan stop and the filmmaker begin?

There’s a constant conversation between those different parts of me. The fan side is a great guiding force at moments, but the fan would love everything to be in the film and that doesn’t tell a story. The director needs to make a film and sometimes you have to be ruthless. When Bruce and Jon made all those albums, they were ruthless in their editorial. They cut off “Fire,” they cut off “Because the Night” — big hits, but they didn’t fit the narrative of that album. So I’ve learned a few things being around these guys and it definitely has an influence on my filmmaking.

Did your friendship with Springsteen pose any challenges?

I never let that take away from the focus. We all go into this with the desire to make the best story, and nothing is personal. Those explorations don’t fall into a personal space. It’s a film. The fan doesn’t cross over in that world. You stay in the zone of being with them, in sync and trying to make the best film possible.

Do you look at things differently after you finish a documentary?

These films carry a space for me to be able to grow as a person. I can look back at different chapters of my life and what I got from the The Promise [The Making of Darkness on the Edge of Town] and that commitment that Bruce had. Or Wings for Wheels [The Making of Born to Run], where things were do or die. Or Road Diary, where it’s acknowledging mortality and how that white light is coming right at us. But you need to enjoy every moment and give your focus to life itself. I’m able to process each one of the films later on, not in the moment. That’s the second part of making these films. Six months from now, I’ll process Road Diary even more.

What was your favorite moment of the tour?

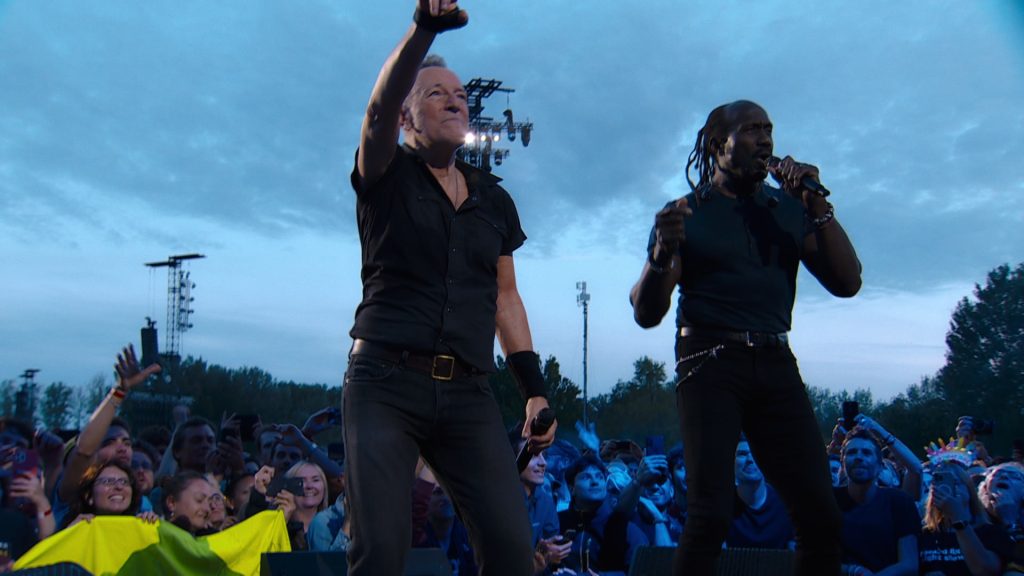

My favorite experience was in Barcelona. I had heard about [the Barcelona fans] from Bruce over the years, but I wasn’t prepared for it. We had just witnessed an amazing performance of “Born in the USA”. I got emotional and everyone in the crew had this emotional reaction. It was a magical feeling of being with thousands upon thousands of people having this moment of unity. The stadium singing back the song was a powerful experience. When I heard the tapes of the crowd singing and matching the level and sound of the band, it took me right back there. Every time I see that in the film, I cherish that moment.